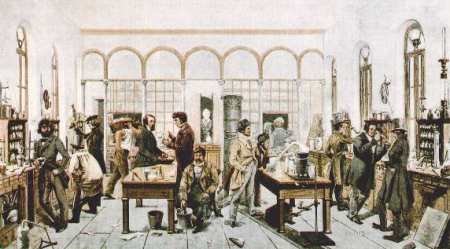

The span of time from about the beginning of the 1st century AD to about the 17th century is considered the period of alchemy. The alchemists believed that metals could be converted into gold with the aid of a marvelous mineral called the philosopher's stone, which they never succeeded in finding or making. They did discover new elements, and they invented basic laboratory equipment and techniques that are still used by chemists. However, the alchemists learned very little that was worthwhile concerning the fundamental nature of matter or of chemical behavior. They failed because their basic theories had almost nothing to do with what actually happens in chemical reactions.

пятница, 3 февраля 2017 г.

The Sterile Period of Alchemy

The span of time from about the beginning of the 1st century AD to about the 17th century is considered the period of alchemy. The alchemists believed that metals could be converted into gold with the aid of a marvelous mineral called the philosopher's stone, which they never succeeded in finding or making. They did discover new elements, and they invented basic laboratory equipment and techniques that are still used by chemists. However, the alchemists learned very little that was worthwhile concerning the fundamental nature of matter or of chemical behavior. They failed because their basic theories had almost nothing to do with what actually happens in chemical reactions.

Подписаться на:

Комментарии к сообщению (Atom)

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий